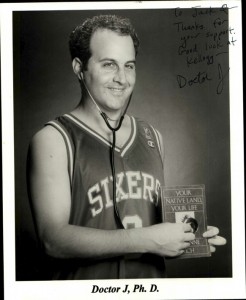

My headshot as “Dr. J” after finishing my PhD, 1997. I’m wearing the Julius Erving Sixers jersey and applying the stethscope to Adrienne Rich’s book. I had an alternate shot in which I wore the mortarboard.

Josh Marshall, the creator of Talking Points Media, one of my favorite politics blogs, is a fellow would-have-been professor who realized that academia was not for him. He has a post up on the latest surge of academia-bashing, which was started by a Nick Kristof op-ed in the NYT on why professors aren’t present enough in public debates on policy or other vital topics. It’s really worth reading if you have ever been in academia…or just wanted to wear a mortarboard! All of it brought me back to my own fortunate escape/rejection from academia, happily not so early that I missed out on taking the righteous headshot you see here.

Josh’s piece takes you step-by-step through the early life of passionate devotion to history, the successful attainment of a top PhD program, and even the early-grad-student successes that would all herald a possible faculty spot. And then the realization that success, as defined by writing for an audience of a couple of hundred people in your field, is just not enough to sustain you through the depressing uncertainties of the serfdom of academia. This passage really rings true for me of what it was like back then, to have the double realization that all this dreaming and success would not be working out, and that even if it did this was not the team I wanted to join for life:

Much has changed and stayed the same since the mid-90s. But consider the sociology of graduate education in the humanities. To get into a strong PhD program you need to be fairly bright and, even more important, you need strong academic credentials. At least then, those attributes gave you a pretty good shot at a life of at least some and maybe a lot of financial comfort and stability. Law school, medical school, consulting, business or other opportunities.

In this case, you’re spending at least 5 or 6 years in school with the distinct possibility you’ll never get a full-time tenure track position. Think about it, the better part of your twenties for the chance to get a job. If you do get a job it will likely be somewhere you’ve never lived or wanted to live and your main goal will be working like crazy to build up enough publishing capital to move on to some other more desirable position. Many end up piecing together various contract positions with little prospect of finding a permanent job with a future, benefits or anything. Needless to say, this can be a bit depressing. And all the while folks are seeing their college peers getting their first adult incomes in various professions or business or whatever else.

Perhaps unsurprisingly this can generate some pretty toxic intra-group dynamics. And the negativity this involves, I think, pervades a lot of academic life.

He goes on to describe the familiar tropes of self-isolation, questionable relevance and futility that have described academia for so long–but from the refreshing perspective of someone who realized against the odds that the training he was getting could be applied to a different pursuit. As he puts it, “all the incentives of academic life drive against having the time, the need and in many cases the ability to communicate with a larger public.” I think this is a needless tragedy to befall so many committed and smart PhD students, but the forces of self-replication among graduate faculty are strong.

I had my own example of this phenomenon about eight years ago. I was six years into my post-tenure-track-aspirant career as an academic administrator at MIT, and sitting, in fact, as a visiting something or other at Cambridge University while part of a collaboration between Cambridge and MIT that Gordon Brown started.

I wrote a note to the graduate chair of my old English Department to reflect on my path out of the would-be-faculty and into a related career that was using much of what I learned, and which current grad students might do well to at least hear about. He agreed that this would be valuable, and said he’d actually gone and gotten a grant the previous year from the Woodrow Wilson Institute to pilot just such an effort. Two PhDs joined him to lead a class that was intended to teach English grad students something about how they could apply their toolkit (forbidden term in humanities, mandatory in biz world) to interpret and communicate outside of academic research.

This really wasn’t looking to push people too far out of their chosen paths, I don’t think, but just broaden the perspectives of those who were darn well going to stay in academia. Sadly, only a handful of students signed up, and my professor said that he didn’t see any appetite amongst those motivated to get into the department for a career as anything other than an English professor. I can’t imagine it has changed too much since then.

For me, getting nudged out of the professor path by life events and academic hiring practices was very fortunate, because unlike Josh Marshall I didn’t have a strong vision of something else I wanted to pursue. But while his piece is about a debate over the impact of successful academics in the public arena, I think the broader question is how the far greater numbers of people like me who didn’t make it can apply our passion and the analytical tools to make a living and benefit society.

Great post. Although not full-time, I’m glad I found the Clemente Course, which is a bit of a haven for PhDs who want to engage with a wider community but are on “alternative” paths.

By the way, there is now a slew of programs on non-academic PhD careers. On Twitter, check out #postPhD and #postac. A friend just did a panel on non-academic paths for PhDs at the history conference in DC.

Things are changing.