Fantastic promo cover tied to this year’s Alan Ladd “Gatsby”…I mean the 1949 version. Credit: twentytwowords.com

With the advent of the Baz Luhrmann “Gatsby” movie, I summoned up all of my crotchetiness and decided not to see Leonardo light it up Jay-Z style, but rather to reread the Authorized Text in a paperback sitting right here between Faulkner (another Hollywood booze-drowned author) and Flaubert (Baz Luhrmann’s next subject). Have to say I loved Baz’s “Romeo and Juliet,” with the divine Clare Danes and great music, but 20 years later am feeling a bit more “get off my lawn.”

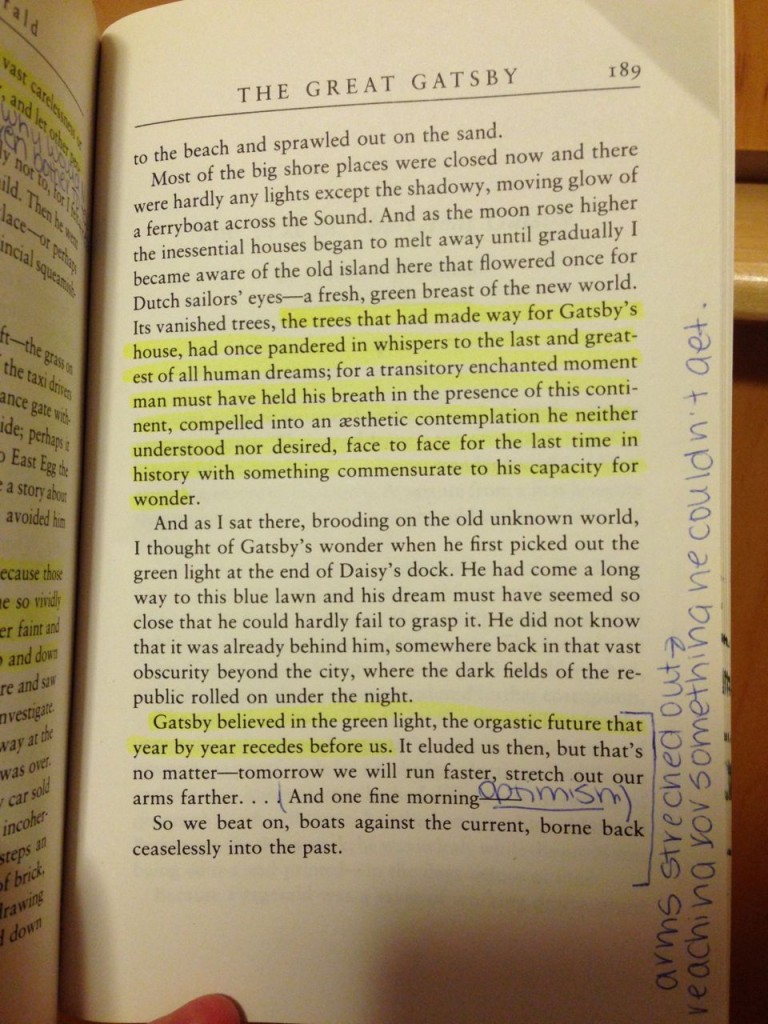

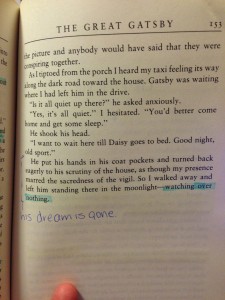

“Gatsby” is really just a long afternoon’s reading pleasure of foredoomed, beautiful attitudes and outfits: plus, as high schooler “H. Brown” pointed out maybe 15 years ago when she read the book, “irony.” Rereading it on the train, I was at first annoyed by her aqua highlighting and her rounded annotations, the letters marching up margins like dutiful bunny siblings in Beatrix Potter. But after a while I was able to bring myself back to the place of a kid taking on a Set Text for the first time, in a pre-Internet era when you were kind of on your own with the words. I remembered making these cipher-like shorthand comments like “Irony,” or “Description of Gatsby,” and thinking that I’d made a significant first step at analysis. Then came the realization that there were still many more words to write to fill out the scarecrow of my “irony” sentence, along with the nagging sense that irony was both less and more than the saddle I would try to throw athwart ol’ F. Scott’s burnished sentences.

Final page, on which H. Brown doggedly saw optimism, and Adrienne Rich found the title for her 1995 collection, “Dark Fields of the Republic”

The other nice thing about sharing a palimpsest-like version of Gatsby with “H. Brown” is a reminder of the community of readers. This is not something that comes across for me on an e-reader. When I read something on a Kindle and come across a passage that thousands have “annotated” before me–probably dropping rich assortments of links to their own stinkin’ literary blogs!–it is a micro-rating system, informing me that 954 people gave an instantaneous “thumbs up” to “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” So far I haven’t yet found any interest in what others have annotated, or in joining their e-highlighting. But on this final page of “Gatsby,” I felt more a part of the history of readers coming to the novel with their own histories and abilities. I can only imagine that “H. Brown,” now maybe in her early thirties, has become acquainted with how Americans say “One fine morning…” to themselves about the most impossible outcomes, and that the optimism she saw then is tempered by age and loss, though hopefully not lost.

And just above this penultimate paragraph, in which Fitzgerald switches from what Gatsby felt to what “we” Americans feel and yearn, is the beautiful evocation of the dark fields of the republic–rolling past the Eastern cities and along out to the sparse towns of Minnesota and points west. This passage gave Adrienne Rich the title for her 1995 collection, but her desire to look across the whole of America and its people is obviously a theme that runs through her work for many years before that. Reading this copy of “Gatsby” in parallel with H. Brown is a palpable reminder that enduring books convene readers across huge gaps in time, experience and self-understanding.

I immediately recognised H. Brown’s handwriting. I have a paperback copy of The Complete Plays by Christopher Marlowe, in which Doctor Faustus (but not Tamburlaine, Dido etc. – the reader only bothered with the set text) is annotated in an identical rounded hand, albeit by a different person on a different continent. The (inane) marginalia in question date from the 1980s. Since then, however, we have entered the post-marginalia age, and henceforth material traces left by readers will become as rare as cuneiform tablets. Indicative of this new order is the fact that the “materiality of texts” now seems to be a specialist academic niche (see recent studies such as The Torn Book: UnReading William Blake’s Marginalia), rather than an unremarkable part of ordinary everyday life.