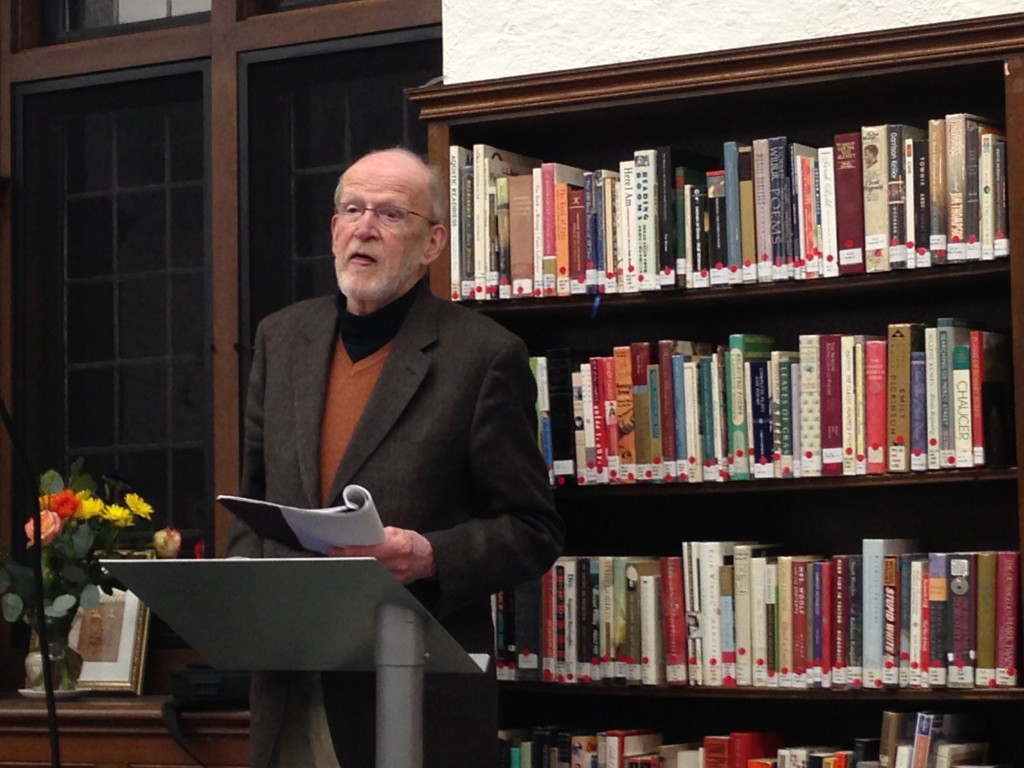

David Ferry reads at the Waban Library Center in Newton, MA, on March 20, 2013 (delightfully, the works of Richard Wilbur and Sylvia Plath AND a Nancy Drew book are in the shelves behind him. Thanks Mr. Dewey!)

Last week I had the great privilege of seeing poet David Ferry read at the community-run Waban Library Center. This charming space is led in good part by the person the Boston Globe called its “volunteer coordinator, community liaison, and biggest cheerleader”: my mom! Another volunteer at the library, Marcia Karp, knows David Ferry from poetry circles and also read her work that evening.

In 2011 I attended a seminar at Amherst on James Merrill and David Ferry’s poetry, put on by my old advisor, David Sofield, plus visiting professor Richard Wilbur. At the time Ferry’s book Bewilderment was still in galley proofs, and he allowed the seminar group to read several works from it. Ferry won the National Book Award last year for Bewilderment, and it got a brilliant writeup in the New Yorker by Dan Chiasson, Amherst ’93. Chiasson in a way is Ferry’s successor as Amherst Poet Dudeman On Campus at Wellesley College, and graciously did an interview with me before the Amherst seminar.

Waban Library Center volunteer coordinator Alice Jacobs describes the library to guest poet David Ferry, March 20, 2013

Ferry is a poet and scholar of humbling talent, and a marvel of togetherness and productivity at 89. He is also a truly gracious man, which I am most struck by today in terms of his poems in Bewilderment that recall his late wife, the critic Anne Ferry. Ferry read his translation of the Aeneid, Book VI, a scene in which the souls of the unburied dead mill about on the banks of the Stygian marsh, waiting for a hundred years to be ferried across by Charon, that “longed-for crossing.” The next poem in the book is “That Now Are Wild and Do Not Remember,” which as Ferry said builds on the scene from the Aeneid, Sir Thomas Wyatt’s poem to a lost lover, “They flee from me,” in order to define his mourning in terms of being “dislanguaged.”

Where did you go to, when you went away?

It is as if you step by step were going

Someplace elsewhere into some other range

Of speaking, that I had no gift for speaking,

Knowing nothing of the language of that place

To which you went with naked foot at night

Into the wilderness there elsewhere in the bed,

Elsewhere somewhere in the house beyond my seeking.

I have been so dislanguaged by what happened

I cannot speak the words that somewhere you

Maybe were speaking to others where you went.

Maybe they talk together where they are,

Restlessly wandering, along the shore,

Waiting for a way to cross the river.

—”That Now are Wild and Do Not Remember,” from Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations

I was so uplifted and haunted at the same time by Ferry’s movement between the erotic register of Wyatt’s poem and the agonizing suspension of the souls in the Aeneid. He is so at home in the formal possibilities of poetry that it is precisely at the “turn” of this near-sonnet that he utters such a powerful line on his own lack of any resolution: “I have been so dislanguaged by what happened.” On this day when the US Supreme Court is arguing the legal merits of recognizing marriages by same-sex couples, it seems fitting to honor this record of a long marriage, and see this evidence of how it is through such loving relationships that people (of all kinds, goes without saying) can come to define themselves at the most basic levels of language, identity and self-understanding.