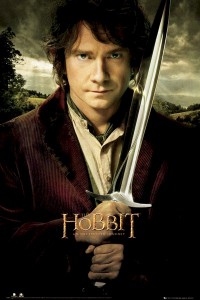

This time of year, Amy draws upon her vast reserves of positive emotional energy to rise above how pale and exhausted we look and lead her women’s gathering posse through various start-your-year-right exercises. By the time we realize it is spring somewhere else, the group will be armed with a vision board and a Word of the Year to hold up like Sting against the orcs that plague the year’s cave tunnels.The impact that Amy has had on this group over ten years is at the level of a shamaness or a powerful anti-depressant, so I have taken a Fake It Till You Make It approach to thinking about these activities. Something must be very right here!

The vision board exercise is actually helpful in getting out onto the page all of the dimensions of your life that need attention. Amy and I find ourselves periodically subject to a willful not-seeing when it comes to the piles of stuff temporarily stacked for months at a time in various places around the house, or the serious monthly conversations about budgets and careers that are missing from the post-bedtime calendar. It’s still early enough in the year that we might yet at least see what it is we need to address.

These past few weeks I’ve enjoyed a flood of beautiful writing in The Awl on how it is we come to grips with not having an answer to everything. Not exactly advice to let go of trying, but to recognize that we as adults are all in the same boat in our inability to get it all right at all times: a realization which (optimistically) could help us all get along better.

At the same time, I’ve been reading application essays to my graduate program at MIT. One of the essays asks candidates to talk about how they dealt with a setback, and the range of responses has been an interesting window into how people frame themselves for the MIT audience. Some of these responses are deeply, surprisingly personal: losses of parents, spouses, careers for people still in their 20s. A few of those who disclose these traumas are able to spin them as somehow helping point their way towards MIT; for a few others, who may be outstanding engineering graduates and leaders of people, but are not as polished as some who have been in the application rat-race all their lives, the losses are still raw. The dichotomy between these earnest efforts to talk about the worst traumas in life and the other essay responses–about why you want to work in manufacturing, for example–points to the challenge of talking seriously about loss/failure in the context of an application package that seeks to prove you are a future Chief Operating Officer

Ironically, MIT is a bastion of “fail fast,” a watchword in the entrepreneurship “space” (I love using that word, which sadly has nothing to do with the return of Vejur to the Solar System). The idea of “fail fast” is that a good entrepreneur will egolessly recognize when their brilliant idea, sunk costs, and many weeks of all-nighters have come to naught and will cut the cord to move onto the next great thing. But this ideal coexists at MIT with a long history of student suicides: people who arrive never having failed at anything, and, confronted with a campus full of people smarter than them, can’t figure out what their lives are worth. Perhaps it is those who can survive this shock to a youthful genius’ ego and keep going that are best suited to joining the fast-fail entrepreneurial elite.

For the prospective MBAs who describe themselves as people for whom “failure is not an option,” and indeed for all of us at this season, our old friend Elizabeth Bishop has some great advice that keeps growing on me. What I love about this poem is that she talks about increasingly profound losses–from car keys to home countries and her beloved–with a kind of studied off-handednesss. This casual grace is all the more striking given that she conveys it through a really challenging form (the villanelle). Most of the students I’ve gotten to know are at a place in their lives where the art of losing is quite distant–though parallel–to the science of failing fast. For them and all of us, let’s hope the scorecard for this New Year’s resolutions is not a disaster.

ONE ART The art of losing isn't hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster. Lose something every day. Accept the fluster of lost door keys, the hour badly spent. The art of losing isn't hard to master. Then practice losing farther, losing faster: places, and names, and where it was you meant to travel. None of these will bring disaster. I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or next-to-last, of three loved houses went. The art of losing isn't hard to master. I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster, some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent. I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster. —Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident the art of losing's not too hard to master though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster. From The Complete Poems 1927-1979 by Elizabeth Bishop, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Copyright © 1979, 1983 by Alice Helen Methfessel. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved.

What’s in a Vegan chimichanga? or don’t we want to know?